Tpettis@foghornnews.com

You’re going to get two things before you walk out of Sam’s Barber Shop. First, you’re going to hear “the good news,” and second, you’re going to get a great haircut.

The rust-red building located in the middle of Hillcrest has long been a hotspot for the community.

“Thank you Lord for giving us another day on this earth,” says Sam Johnson, also known as Sam the Barber. Johnson is the owner of Sam’s Barber Shop and has been cutting hair on the Northside since 1953. He has seen all the changes — from the good to the bad.

“During the ’50s and ’60s businesses were booming,” Johnson said.

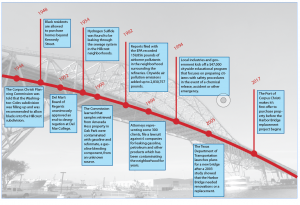

Desegregation began in the 1950s and slowly through time the community started falling apart.

During this time Del Mar College allowed its first African-American students to start taking classes on campus.

Drive around the Northside now, and you will be hard pressed to find a thriving business.

“Residents with the financial ability to move out of Northside started to move out the neighborhood and move to other communities,” Johnson said.

The next major change was during the 1960s through 1970s, with the building of Interstate 37 going right through the neighborhood.

“In the 19 century quite often railroad lines were used to divide neighborhoods and communities along racial and ethnics lines,” said James Klein, associate professor of history at Del Mar College, “and in 20 century it was interstate highway. You can see it in Chicago, Atlanta and even in corpus Christi.”

The residents who didn’t have the financial ability to move out became stuck between the refineries, I-37 and the port. They became blocked off from the rest of the city and forgotten.

“It seems to me that the city has intentionally or unintentionally really forgotten that neighborhood for quite awhile now,” Klein said. “You can see it in the lack of city services out there.”

Over the years Environmental Protection Agency reports started showing the harmful effects the refineries were having on air and water. You don’t need EPA reports to notice the ground is poisoned. All you have to do is look at the orange trees that bear fruit so poisoned it’s inedible.

“We know that there are petrochemicals in air and water in the Hillcrest area,” Klein said. “This is an issue of environmental justice and I think environmental health equals human health”

For Sam the Barber, he noticed the biggest changes started happening during the ’80s

“As some of the old businessman started to pass off, their children didn’t keep the businesses,” Johnson said. “Once the community starts to move and the businesses start to close it makes even more people want to leave.”

From the 1980s through the 2000s a big push from the industrial district to buy out residential land took out another chunk of the community.

According to the Census Bureau, between 1960-2000 the number of owner-occupied units dropped from 700 to 350.

For Pastor Henry Williams, a longtime resident and leader of the community, things aren’t so cut and dry.

“I wouldn’t say that it (I-37) was destructive to the neighborhood although many people would say that,” Williams said. “There’ some that say it divided the community. I don’t know that I have ever had that impression, you know, because it has always been there in my memory. Once I got out of the service it was there.”

Williams, however, recalls a time when the neighborhood was thriving.

“There was a lot of business activity on Staples Street at one time,” he said. “There were young professionals living here. The residents had a great deal of pride because it was one of the first black neighborhoods.”

When the city desegregated, people started to move out of the neighborhood into places closer to where they worked. That is when Williams says the decline of the neighborhoods started.

“There came a time when the sense of pride may have begun to diminish. When the young professionals left they weren’t replaced by people with the same sense of pride,” Williams said.

According to Williams, environmental issues also began to plague the area, causing more people to want to leave and the neighborhoods continued to decline, “but there are those of us who have been here for many years,” he said. “This is home, OK? I’m in prayer about doing the right thing, but this is home.”

With buyouts and relocations approaching, residents are seeing the final changes coming.

“It’s time. You can’t stop progress. You might hinder it for a while but progress is going to come,” Johnson said. “It’s been a wonderful career for me. I loved it, I raised a family. This has been my dream and I have lived my dream.”