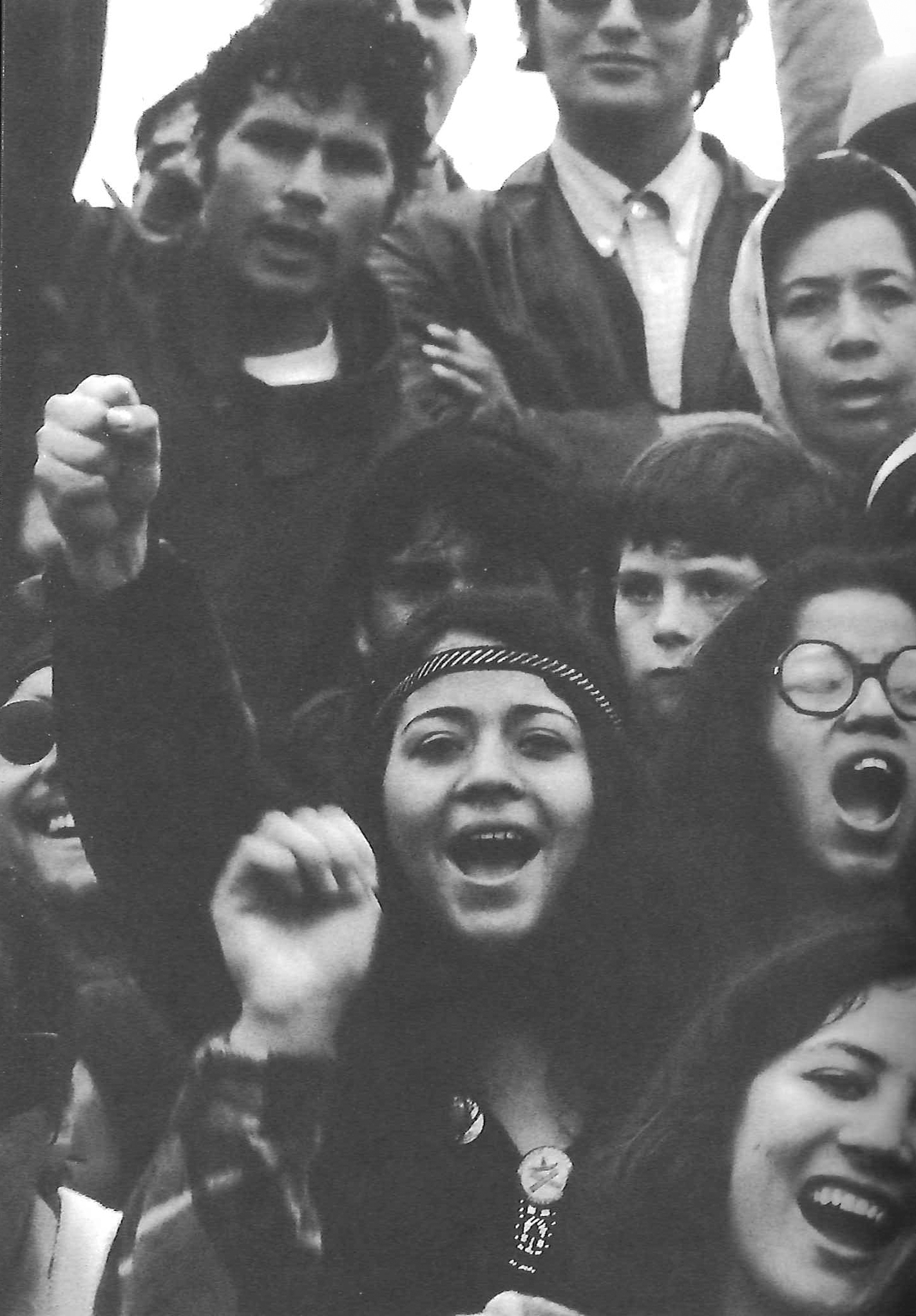

You are a Chicano before you are a woman — at least many females felt that way during the early inception of the Chicano Movement, which ultimately led to the separation of Mexican-American women fighting for their rights independently from Chicanos.

During the 1960s-70s many Mexican-Americans were fed up with the challenges they faced through political, economic and social injustices.

The word “Mexican” was associated with the word “dirty.” People claim no respect, no status was given to them for how they looked and talked.

“I hated being Mexican,” said Moctesuma Esparza in the documentary “Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement.” Esparza highlights how a large portion of Mexicans were only working in labor jobs for the United States.

In South Texas a large majority of residents were of Mexican descent, many of whom were migrant farmworkers with little education receiving low wages. Poll taxes, literacy tests and gerrymandering voting districts restricted Mexican-Americans from taking a political vote. Several Mexican Texans did not have the money to pay for a poll tax and if they did they did not want to vote for white candidates who did not represent their needs.

In 1970, a firm Mexican-American political party, Raza Unida, challenged the dominant white candidates in Crystal City, Texas. Chicano activists José Ángel Gutiérrez and Mario Compean were co-founders of the party and organized rallies for the Mexican community in Crystal City.

Raza Unida was one of the many groups that pushed for the Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement to be heard. The movement focused on a broad cross section of issues, all working toward ending racism; however, Mexican females were often not included or simply were not credited for their contribution within the Chicano Movement.

The Chicana feminist movement included ending common stereotypes and low wages, and voicing the struggles of Mexican women.

‘MACHISMO’ ATTITUDES

While the Raza Unida political party was making a name for itself, the greatest support was among women. One of the founding female members of Raza Unida Party, Luz Gutierrez, said in the documentary about 95 percent of the people who were registering voters and getting people out to the polls were women, yet they didn’t have a say in the decision making.

Gutierrez and Chicanas walked into one of the Raza Unida meetings to declare a position in the party, although the men said “they didn’t want the tamale makers and workers … to be part of the decision-making,” Gutierrez said. Soon men broke off and did not want to be a part of the movement if women were involved.

In search for a Chicana feminist perspective, Chicanas displayed frustration and anger against the “machismo” (strong or aggressive masculine pride) attitudes that occur in Mexican culture and in the Chicano movement. This behavior, typically by men, was a big reason for the shift in Chicanas creating their own organizations.

A great significance to the Chicana Movement was the first national conference for Mexican-American women, which took place in 1971 in Houston. More than 600 Chicanas attended the conference, known as Conferencia De Mujeres Por La Raza.

The conference discussed legal abortion, birth control and the discrimination of gender in the movement and in traditional Mexican households. A survey in the prominent Chicana magazine Regeneración found that “84 percent [of Chicanas at the conference] felt that they were not encouraged to seek professional careers and that higher education is not considered important for Mexican women.”

BATTLING OPPRESSION

Many Chicana writers in the ‘70s were voicing their opinions on the misogyny that takes place in Mexican culture. Mirta Vidal writes in her expose “Chicanas Speak Out — Women: New Voice of La Raza,” that “Chicanas, along with the rest of women, are relegated to an inferior position because of their sex. Therefore, Raza women suffer a triple form of oppression: as members of an oppressed nationality, as workers, and as women.”

It is Chicanas today, in the movement today, that take the reins of many ideologies through literature.

Possibly the largest female figure from the Chicano Movement was Dolores Huerta, known as a civil rights icon who fought for the rights of farmworkers. Her work is often overshadowed by Cesar Chavez; even the famous phrase Huerta came up with, “Si se pierde,” is coined to Chavez. In fact, many men in the movement called her his sidekick.

The Chicana movement within the Chicano Movement presented the need to be liberated from traditional female/male roles.

As the Chicana Movement has continued on into modern day, there’s still a sense of “machismo” in Mexican culture, though the movement continues to voice its concerns through the arts, music, social, political and economic injustices.

In Corpus Christi, there’s a rising Chicano Mural Movement that many artists contribute to. One specific artist, Sandra Gonzalez, who painted the colorful “Endless Sunset: The Colors of Our City” on the Caller-Times building, focuses on Mexican culture through her work.

It’s important to know where these movements come from and what they have and haven’t accomplished. The following “Way Back When” articles will continue to be a focused series on women’s rights.

One thought on “Chicanas fight oppression then and now”