Like many immigrants, getting to the United States was only half the battle for Perla, a recent Ray High School graduate now attending Del Mar College. Once in her new homeland, the anxiety, fear and uncertainty only grew.

Though Perla entered the country legally at age 13, she spoke no English and had a difficult time in school.

“People would tell me I couldn’t make it and I would cry a lot because I didn’t have a Social Security card, but I knew I had to go for it,” said Perla, who didn’t want to give her last name because of lingering fears.

While the United States struggles to keep the borders secure and prevent or at least slow the flood of undocumented immigrants into the country, many migrants struggle with the uncertainty and reality of being deported. The uncertainty can be attributed to multiple factors — they’re in the U.S. illegally, they’re here legally but the culture shock and pursuit of happiness is not what they expected, the process is stacked with what seems like never-ending paperwork and filing fees are nothing short of overwhelming.

One of the many things we often take for granted no matter the physical price is the value of an education. For Perla this value is priceless. It is something many people cannot understand. How could anyone in this world not make it beyond elementary school because our parents and their parents couldn’t afford the cost of an education? Many people south of the border dream of coming to America with the optimism of a better life and a bright future, much like the dreams many Americans have when they want to experience Spain or Paris.

There’s a clear difference though between these dreams that are filtered by the U.S./Mexico border; one is for recreation and the other, opportunity. It’s hard to grasp the concept of being limited to what you can achieve in life and it’s for this reason so many people migrate into the United States.

Wanting to provide for and to offer his family more, Perla’s father took that risk of crossing into the U.S. He made the journey into America on a couple of occasions including one time with the aid of a human trafficker, or “coyote” as they’re referred to, only to return each time back to his family in Mexico. By the time she was 13 years old her mother and father had finally saved enough money and completed the confusing process of getting a visa so they could all enter the country legally as a family. Perla said that after arriving her father told her to “do her best because an education is the most important thing in life.”

Perla continues to hold her father’s words close to her heart while the memories of heartache and despair linger closely in her mind. That early adversity has made her stronger and drives her to be better and do better. She spends her free time helping other children who have migrated into the United States. Perla mentioned a young girl, who, much like her when she arrived in America, doesn’t understand English. She said she enjoys helping the young girl because she can “see herself in her” and she doesn’t want her to have the bad experience she did.

Perla said when she first started school her teacher would almost ridicule her because of the language barrier. “She was mean to me and it made me feel like she looked down on me,” she said. “One time she got mad and said I needed to learn English.”

Perla, however, is achieving her goal of getting an education and in the process made her mother and father proud by completing high school. She is enrolled in college and strives to move even further.

“I want to be a bilingual teacher because I don’t want people to go through what I went through,” Perla said.

While optimistic about her future, Perla is uncertain about the rest of her family who still live in Mexico. Her hometown, like many south of the border, is trapped in a Mexican drug cartel war zone.

“The last time I went to Mexico was about 4 years ago with my mother,” she said.

She said the trip nearly ended in disaster when Customs and Border Protection detained them for a whole day when they attempted to re-enter the United States. This process isn’t uncommon because of current U.S. visa laws.

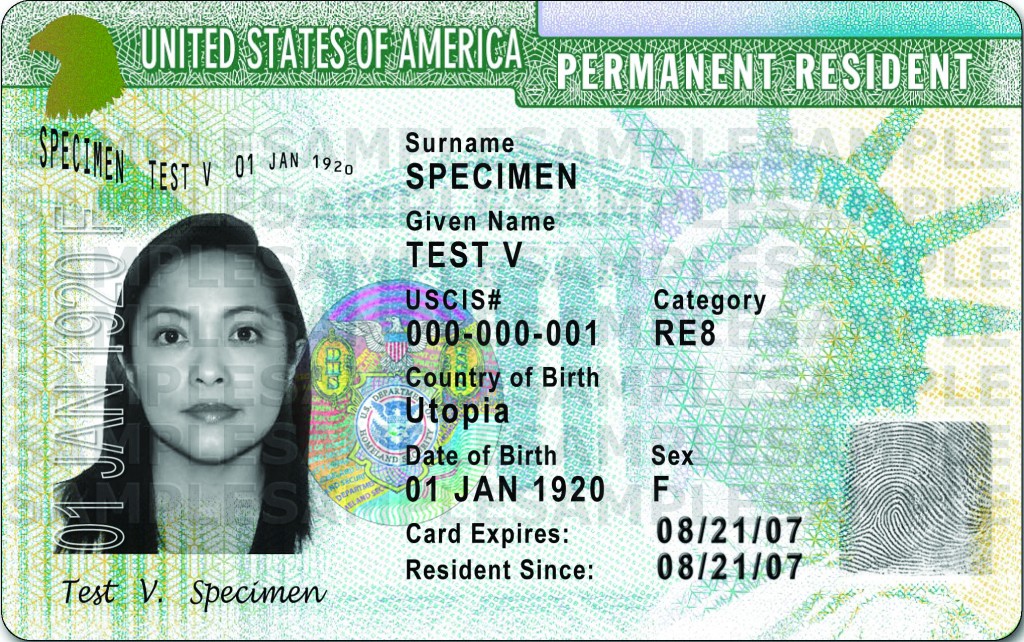

The hardened process for obtaining a United States visa, green card and even citizenship compiled with ramped up border protection took place after 9/11, but has steadily continued to change since the birth of the Obama administration in 2009. However, major changes to the immigration process took a turn in 2010 and then were updated even more in 2014. I can’t say America is coldhearted — after all I was born here, I fought for my country and can remember a time when I didn’t Deutsch sprechen, but for a noncitizen the process it takes to get that piece of plastic in their hands that’s says, “Hey! I can finally have a better life and be whatever I want to be and take care of my family” is in short, nerve-wrecking.

The United States offers 15 different visas a noncitizen can apply for and offers three subcategories. Simple? Not so fast, you need to figure out if you’re a B1/B2, BBBCV, an H, an L, maybe a T, or even a C, just to name a few. The U.S. does try to make the process user-friendly while leaving those wishing to obtain a visa the task of completing the process in just four steps. The hard part comes when filing the actual paperwork and it appears as though every filed paper has a fee attached to it. Because the process could be difficult and costly (hundreds or thousands of dollars), especially when multiple family members are involved, the United States Embassy recommends noncitizens to use an immigration attorney to help ease the process.

A United States visa does not guarantee access into the country. Perla said her family is afraid to try to return to Mexico because they’ve all worked so hard to be here.

“I’ve heard the stories of people not making it and kids dying,” she said. “I remember when I was 9 we were all scarred because we didn’t hear from my father in about three weeks.”

Although the stretch across the desert into the United States is relatively short, many migrants don’t survive the trail. Their remains lay in the dirt until one day someone finds them. Many of them remain Jane or John Does. Some of them, if identified, are returned to their families for a proper burial, while the others sit unclaimed, undocumented.

To those reading this column, I challenge you to this: Take a moment and go back over the words you may have blindly passed by and think about what it would be like to NOT be a U.S. citizen. Do you find yourself thinking that yes, maybe I do take the privilege of being an American for granted? Do you think you would still want to be here? Think about being born in the United States in the same likeness of flipping a coin, “And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air?” maybe — then again, that same coin could have landed on tails.

C. Robert Gonzalez has several years’ law enforcement experience, including three years with the Nueces County Sheriff’s Office. He is also an Iraq War veteran and served five years with the U.S. Army. He now is a Del Mar College student.